X: @vivekbhavsar

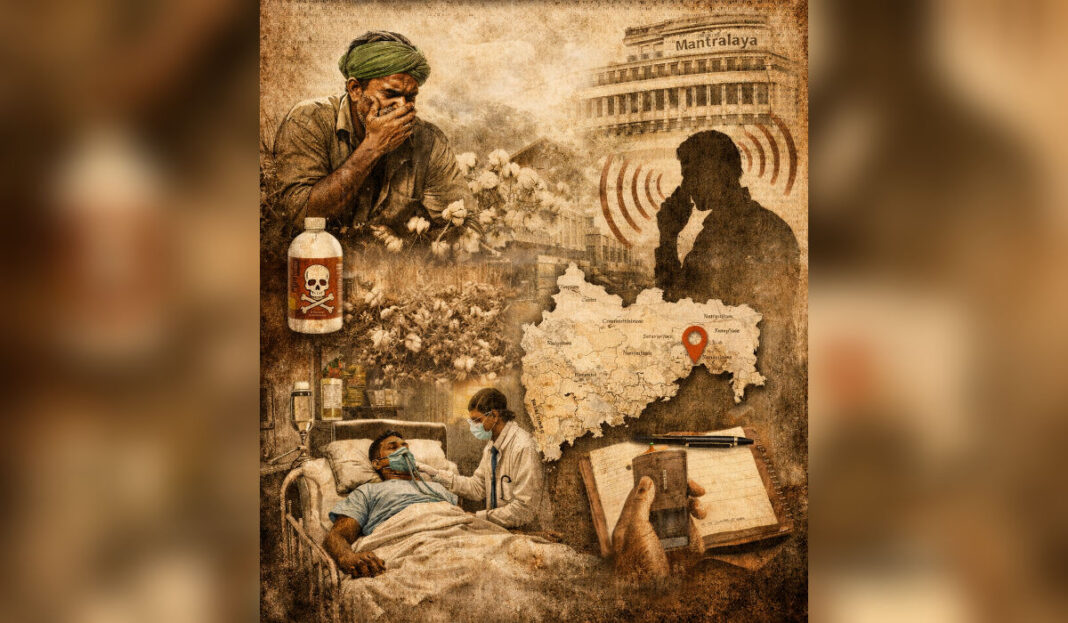

Mumbai: Yavatmal did not become a symbol of pesticide poisoning in one season. It became one because the warning signs were visible much earlier but were quietly ignored. While reporting from the cotton belt for an English daily years ago, I began receiving information about farmers collapsing in fields after pesticide spraying. Hospitals were admitting patients with similar symptoms — breathlessness, excessive sweating, vomiting, convulsions. Yet medical records carried a vague entry: poisoning. No mention of the chemical. No pattern acknowledged.

To understand what was happening, I spoke to the district administration. The discussion was detailed and factual. It covered hospital admissions, pesticide spraying practices, the pressure on farmers during the cotton cycle, and the limitations of the response system. There was nothing unusual about the call. No press briefing followed it. No official communication was issued. Within minutes of that conversation ending, my phone rang again.

Also Read: Iqbal Singh Chahal to Lead Mumbai Police Housing Township Project

This call did not come from Yavatmal. It came from the power centre — the sixth floor of Mantralaya. The tone was calm, even courteous. There was no threat, no instruction in writing. Just a suggestion that the story need not be pursued. The message was subtle but unmistakable: this was sensitive territory.

I went ahead with the story. But before publishing, I asked a simple question — one that has stayed with me ever since: how did the system know, almost instantly, that a journalist was working on pesticide poisoning in Yavatmal? There had been no public disclosure. No formal communication. No official trigger. The speed with which the information travelled said more than the phone call itself.

Yavatmal, it was clear, was not just a local issue. It was already a problem that made the system uncomfortable.

Years later, the national conversation has finally caught up. Reports now acknowledge what was visible on the ground long ago — that acute unintentional pesticide poisoning is widespread, underreported, and poorly tracked. Maharashtra was not an exception. It was an early indicator. What stood out during my reporting then — and still does today — is how cases were recorded. Hospitals treated patients without knowing which pesticide was involved. Files noted “poisoning” and moved on. Without chemical identification, treatment became guesswork. Surveillance remained weak. Accountability never took shape.

This was not because doctors were indifferent. It was because the system had never been designed to capture the full picture. When uncomfortable information surfaces, governance does not always respond with denial. Often, it responds with discouragement. Not through formal orders, but through signals. Not through censorship, but through hesitation. That is how many public health crises remain invisible for years.

Yavatmal was one such moment — a point where evidence was available, suffering was visible, and yet silence was preferred. The recent national discussions on pesticide poisoning confirm what was evident even then. Highly hazardous pesticides continue to circulate. Farmers remain exposed. Medical systems remain underprepared. Data remains fragmented. The cost of this delay has been paid quietly — in rural homes, in district hospitals, in lives that never entered national debate.

This story is not about confrontation with authority. It is about memory. About recognising that warnings often arrive early, but action arrives late. If Yavatmal is remembered today, it should not be as a tragedy alone. It should be remembered as a moment when the system knew — and chose not to listen loudly enough.

QQ88 là nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến uy tín, tối ưu tốc độ truy cập, giao diện mượt và trải nghiệm ổn định cho người dùng.

I wish I had read this sooner!

Thank you for sharing this! I really enjoyed reading your perspective.

You really know how to connect with your readers.

It’s great to see someone explain this so clearly.